Feeding yeast to rainbow trout as a sustainable feed

Yeast grown on food waste is a good protein feed for farmed rainbow trout, and can replace 40 percent of the fish meal used today. Higher proportions may reduce growth and the cause seems to be anemia, which is probably associated with the yeast's high content of DNA and RNA. Also, it is better to use inactivated than live yeast when water temperature increases. These results are presented in a dissertation from SLU by David Huyben.

Aquaculture is the fastest growing food production industry and has recently matched wild catch from fisheries. Salmonids, such as rainbow trout and Arctic charr, as well as other carnivorous fish, such as Eurasian perch, require high levels of protein in their diet to maintain adequate growth.

Soy and fish meals are currently used as main protein sources in these diets, but researchers at SLU are now evaluating more sustainable protein sources that don't compete against the food for people. One promising feed is yeast grown on food waste, since it is high in protein, and cannot be used directly as a human food. However, yeast does not appear to be suitable as a single protein source in fish feed, since some studies have shown that feeding large amounts of yeast can reduce the growth of fish. David Huyben from SLU has investigated the reasons for this in a dissertation focusing on farmed rainbow trout.

In his studies there were no signs of negative impacts on fish when up to 40 percent of the fish meal in the feed was replaced by baker's yeast. The uptake of protein was similar, and the fish showed no signs of being more stressed. Yeast, therefore, seems to have a good potential to at least partially replace fishmeal as a protein source and to contribute to more sustainable fish farming.

When 60 percent of the fish meal was replaced by yeast, David Huyben and his colleagues found that fish showed signs of anemia. A possible cause is the high content of DNA and RNA in yeast cells. Humans that consume large amounts of yeast can develop kidney stones and gout, while fish are thought to safely digest larger amounts. But also for fish there appear to be harmful levels.

"A method that reduces the content of DNA and RNA in fish feed would make it possible to mix more yeast into the feed in the future," says David Huyben.

In his work David Huyben also examined the effects of feeding live or inactivated yeast on fish growth and the gut flora. At a water temperature of 11 °C there were no significant differences between these feed types, but it seems to be more risky to use live yeast when farming fish in warmer water. Rainbow trout farmed at 18 ° C showed greater signs of stress, resulting in a suppressed immune response, and feeding live yeast aggravated this problem.

"At higher water temperatures, our advice is to use inactivated yeast," says David Huyben.

Finally, it was also clear that the yeast species that is used matters. Most of the experiments were carried out with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a species often used in baking and beer brewing. However, another species that was tested, Wickerhamomyces anomalus, cannot be recommended, since it disturbed the intestinal flora of the fish. Aside from this yeast, feeding high levels of both inactivated and live Saccharomyces cerevisiae to rainbow trout had little effect on their gut flora and showed that reduced fish growth was not caused by disrupting natural bacteria and yeast populations in the gut.

-----------------------------------

MSc David Huyben, Department of Animal Nutrition and Management, will defend his PhD thesis Effects of feeding yeasts on blood physiology and gut microbiota of rainbow trout at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) in Uppsala on September 8th.

More information

David Huyben

Department of Animal Nutrition and Management, SLU

david.huyben@slu.se

Link to the thesis summary (pdf)

https://pub.epsilon.slu.se/14478/

Press images (may be published without charge in articles about these findings, please acknowledge the photographer).

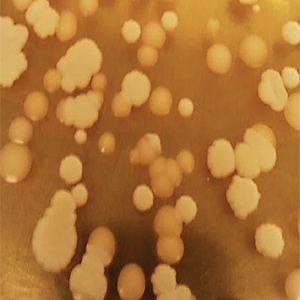

Yeast on an agar plate. Photo: David Huyben

David Huyben in his lab. Photo: Private