High-yielding rice that greatly reduces methane emissions has been developed at SLU

Rice is a staple food for half the world's population, but its cultivation leads to significant emissions of the greenhouse gas methane. Now, researchers from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and colleagues in China have identified two chemical compounds secreted from rice roots that affect the amount of methane emissions. This knowledge made it possible to breed a high-yielding variety of rice that reduces methane emissions by up to 70 per cent.

“This shows that you can have low methane emissions and at the same time get good harvests,” says Anna Schnürer from SLU, who led the study together with SLU colleagues Chuanxin Sun and Yunkai Jin. “Together with Jia Hu and Jens Sundström we also show that it was possible to achieve this with traditional plant breeding methods, without GMOs”.

Rice cultivation is associated with high emissions of the greenhouse gas methane. The reason is connected to small carbon compounds that the plant roots release into the soil in which they grow, and that are are used by various microorganisms. As rice plants are usually grown in water, in an oxygen-poor environment, it is mainly methane-producing micro-organisms that thrive in the root zone closest to the rice plants. And they are the ones causing the methane emissions from rice paddies.

The link between root exudates and methane emissions has been known for a long time, but it has been unclear which chemical compounds are involved. To identify which substances are converted to methane, the researchers compared root exudates from two different rice varieties. One, SUSIBA2, is a GMO variety developed at SLU about ten years ago, which gives rise to low methane emissions after being equipped with genes from barley. The other, Nipponbare, is a non-GMO variety that produces average methane emissions.

Methane is formed from fumarate excreted by rice

What the researchers found was that the roots of SUSIBA2 produced significantly lower amounts of the substance fumarate and also that the amount of methane-producing microbes in the surrounding soil was lower.

To confirm the role of fumarate, the researchers added this substance to soil surrounding rice plants, and this indeed led to increased methane emissions. In addition, they showed that methane emissions from a rice crop can be greatly reduced by adding a chemical (oxantel) that inhibits the breakdown of fumarate.

Ethanol inhibits methane production

Still, the researchers realized that the SUSIBA2 plants gave rise to so small amounts of methane that fumarate could not be the only explanation.

“It was a bit of a mystery,” says Anna Schnürer. “We noticed that the soil itself contained something that reduced methane emissions, so we believed that there must be some kind of inhibitor that also affects the difference between the varieties.

When the research team re-analysed the root exudates, they noticed that the SUSIBA2 rice excretes significantly more ethanol. And it turned out that it was also possible to reduce methane emissions by adding ethanol to the soil around rice plants.

Breeding for high yields and low emissions

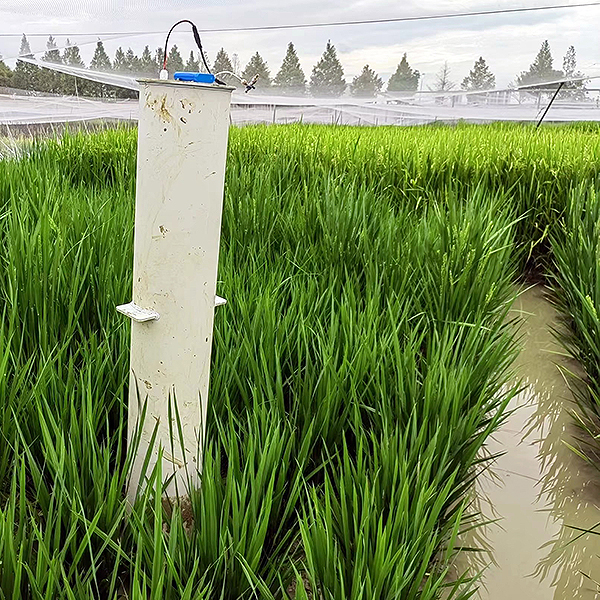

The next step was to investigate whether traditional plant breeding could be used to produce a rice with both low methane emissions and high yields. To do this, they started with a variety they had discovered in a previous study looking for varieties with naturally low methane emissions. This variety, Heijing5, emits less fumarate and more ethanol than normal, but its yields are too low to compete with high-yielding varieties. As a curiosity, it can be mentioned that this particular variety has characteristics that allow it to be grown at northern latitudes, and that field trials have been conducted on flooded fields along the Fyrisån River outside Uppsala in Sweden.

Heijing5 was crossed with a high-yielding variety and by selecting offspring with good yield, low fumarate production and high ethanol production during five generations, they had a material that they could test in field trials in China. The new rice gave rise to on average 70 per cent less methane emissions than the elite variety from which it was bred. Yields were also relatively high, averaging close to 9 tonnes per hectare, compared to the Chinese average of about 7 tonnes per hectare.

The researchers are now working to register the rice as a variety in China and other countries, so that it can be marketed to farmers in the future. They are also working with fertilizer companies to see if oxantel can be added to commercial fertilisers.

“It is one thing to breed environmentally friendly rice varieties, but then it is important to bring them to the market and get farmers to accept them,” concludes Anna Schnürer.

Contact person

Anna Schnürer, Professor

Department of Molecular Sciences

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala

anna.schnurer@slu.se

https://www.slu.se/cv/anna-schnurer/

Research articles

Present article

Jin Y., Liu T., Hu J., Sun K., Xue L., Bettembourg M., Bedada G., Hou P., Hao P., Tang J., Ye Z., Liu C., Li P., Pan A., Weng L., Xiao G., Moazzami A.A., Yu X., Wu J., Schnürer A., and Sun C. 2025. Reducing methane emissions by developing low-fumarate high-ethanol eco-friendly rice. Mol. Plant. 18, 333–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2025.01.008

Characterisation of the cultivar Heijing5

Hu J, Bettembourg M, Moreno S, Zhang A, Schnürer A, Sun C, Sundström J, Jin Y. 2023. Characterisation of a low methane emission rice cultivar suitable for cultivation in high latitude light and temperature conditions. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 30(40): 92950-92962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-28985-w

Earlier progress in the breeding process

Hu J, Bettembourg M, Xue L, Hu R, Schnürer A, Sun C, Jin Y, Sundström JF. 2024. A low-methane rice with high-yield potential realized via optimized carbon partitioning. Science of The Total Environment: 170980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170980

Press images

(May be published without charge in articles about this press release, please include the name of the photographer)

(Top image) Field trials in China, with equipment measuring methane levels in the air. Photo: Yunkai Jin

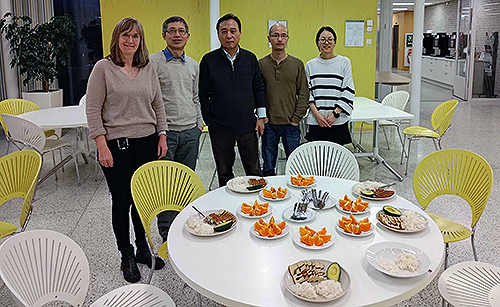

Tasting of the new rice with parts of the research team and funders. From left: Anna Schnürer, Bo Liu, Zheng Fang, Yunkai Jin, Jia Hu. Photo: Axel Schnürer.

Field trial outside Uppsala, Sweden. Photo: Yunkai Jin

Rice in a cultivation tunnel outside Uppsala, Sweden. Photo: Yunkai Jin