Whether green spaces are accessible to all segments of the population is still a matter of research. Many studies from the US and the global South show that poorer neighbourhoods have less access to green spaces than more wealthy areas. This raises the question of whether this trend also applies to Nordic cities. Are green spaces fairly distributed? And are they located where people need them most?

Green Equity Index

The Green Equity Index is a method that makes it possible to analyse the socio-economic status of areas and their access to greenery. The method was developed by, among others, Professor Thomas Randrup and Research Assistant Agnes Pierre from SLU, who spoke about the method and the results during a webinar in the series Venue: Urban Landscapes organized by the SLU Think Tank Movium and the future platform SLU Urban Futures.

The idea is that the Green Equity Index will help municipalities to design cities that are better for both the environment and people. One of the goals was to introduce a quantitative tool for urban planners, managers and decision-makers where they can easily assess how access to greenery compares to socio-economic conditions. The method is based on open data, or data that municipalities have access to, for example, through geodata collaboration agreements. Only basic GIS knowledge is required, which allows almost all municipalities to work with the tool.

Malmö as an example

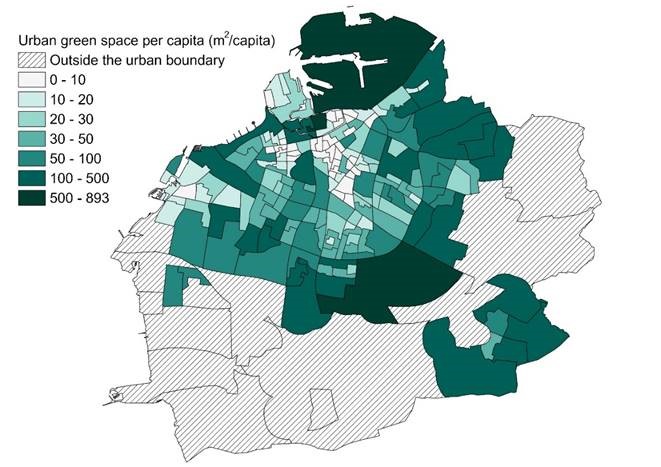

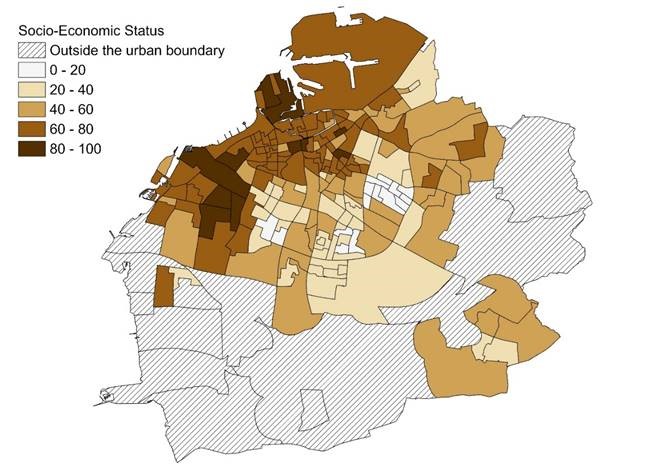

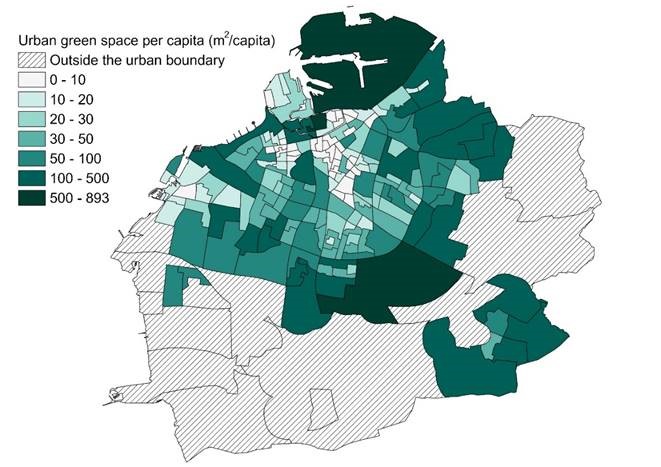

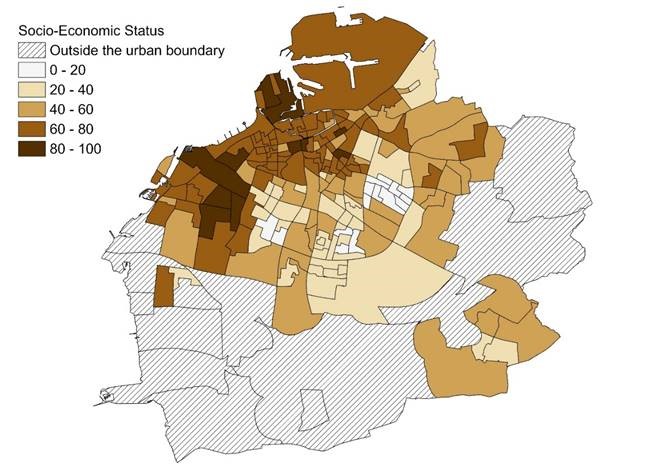

In developing the tool, Malmö has been used as an example. To get a picture of the equity aspect, the researchers conducted a case study with Malmö as a test area. Contrary to research results from other parts of the world, the results of the analysis in Malmö show that areas with a high socio-economic status generally have lower green space status. This applies to both new construction areas and older areas in the city centre.

In Malmö's case, the result is partly due to the fact that the city's million-dollar program areas often include large green spaces, while newly built areas in Malmö's city centre such as the Western Harbor are often densely built-up.

"This analysis provides a starting point for planners who want to identify neighbourhoods where greenery may need to be prioritized. However, you may always need to go in and delve deeper into what needs to be done, how and for whom", says Agnes Pierre.

Ludwig Wahlund Sonesson works at the City of Malmö as a climate adaptation strategist and has been involved in the work of testing the method as part of its green planning. He believes that an equal green policy in Malmö should focus on who is responsible for what we try to use the greenery for, as well as who is most exposed to the risks caused by climate change and therefore has the greatest need for greenery. To understand the risks of climate change, the City of Malmö uses a three-part model in which they consider how serious an incident can be, who is exposed to it and how vulnerable different people are. The City of Malmö has begun to work on mapping this vulnerability to climate change, in particular the vulnerability to heat waves. Heat is one of the clearest risks, which can be minimized through work with urban green spaces, especially by working with increased crown coverage on trees. Similar to the tool for assessing fair distribution of green spaces, a tool is therefore used that shows an indication of vulnerability and extreme heat in Malmö's sub-areas. These two tools are used together to provide better conditions for prioritizing what should be done with the city's limited resources.

"How cities prioritize is often hidden from citizens. This type of mapping, if followed up by political priorities such as the 3:30:300 principle, contributes to transparency. It is important from a democratic point of view to show that we make a choice when we prioritize and that it is clear what we base that choice on", says Ludvig.

In Malmö, the combination of analysing both vulnerability and socio-economic status compared to the access to green spaces shows a somewhat different picture than the one that Thomas and Agnes describe. Here we can see a clear stretch in the central south and south-eastern part of Malmö, where vulnerability is higher for extreme heat, and where one can then see a greater need for greenery. Some of the areas that have increased vulnerability also have a large access to greenery.

"There we may need to work on increased preparedness or more social initiatives to strengthen the residents. We need to look at this with a broad perspective, at several different areas and try to weigh up many different factors in order to be able to make good priorities."

Greenery as a health factor

Emma Franzén, landscape architect and investigator at the Public Health Agency, believes that we must talk about greenery as a health factor since it is very important for public health in general – both for our physical and mental well-being. Based on the Public Health Agency's environmental health survey, it can also be seen that there is a socioeconomic difference in access to green areas, differences that can be based on socioeconomic factors such as country of birth. For example, there is a difference in access depending on whether you were born in Sweden, the Nordic countries, within Europe or outside Europe, but there is an even clearer difference in how much time you spend in green and natural areas. Spending time also differs between different ages, with younger people spending less time in green areas than older people. There is also a difference in gender; women generally spend more time in green and natural areas than men. Education level also has an impact. Comparing survey results with how even the distribution of green areas looks in a GIS analysis can provide more perspectives and create a discussion about how people themselves assess their access to greenery and what is visible on the map.

"It is also relevant to look at whether you can choose where you want to live – you might choose to live in a dense urban area but at the same time have the opportunity to spend warm days in your summer house. This plays a big role from a health perspective, if you are able to change your environment", says Emma.

The webinar ended with a question-and-answer session where questions were asked about how trade-offs between quality and quantity are made when cities change. Here, Ludwig Wahlund Sonesson emphasizes that this is something that must be taken into account when densifying Malmö.

"When we must meet housing needs at the same time as we want to maintain greenery, the trade-offs can be tricky. Here we must bear in mind that a good green status is not permanent but something that must be constantly managed and valued."