The case of Fiby urskog

Since January 2022, the visitor to the nature reserve Fiby urskog (primeval forest) is greeted by a sign:

Warning!

Due to high risk of falling trees, the pathway is closed until further notice and will not be maintained. Visitors enter at their on risk.

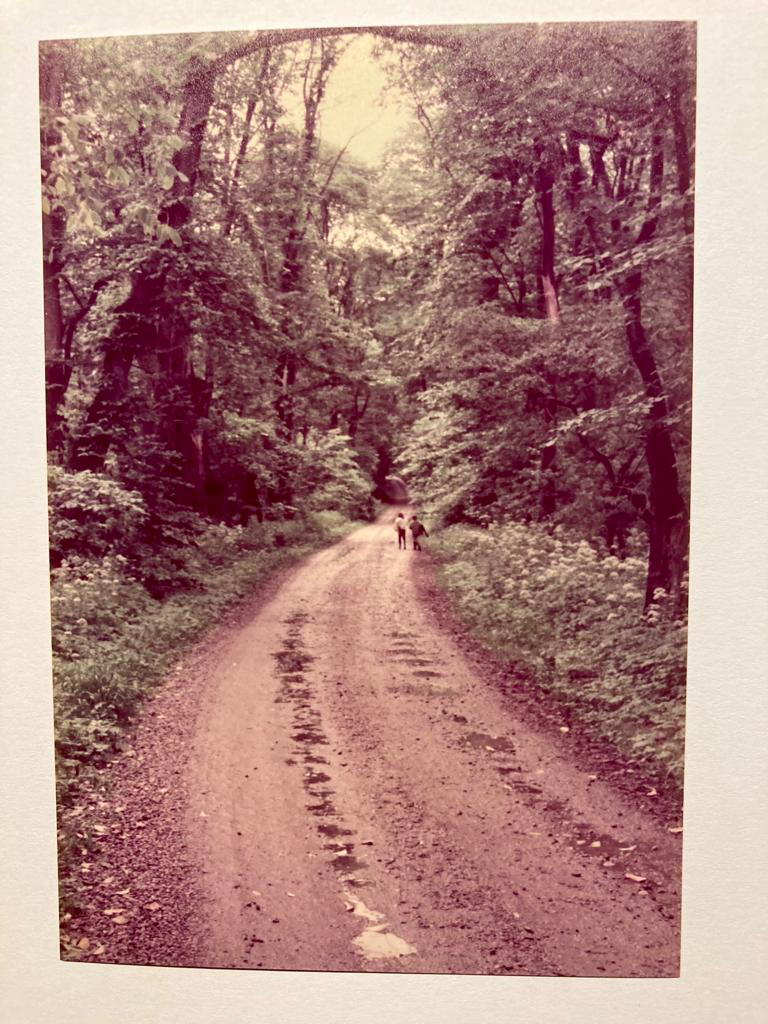

Fiby is an 87 hectares large natural reserve west of Uppsala. It is a typical primeval forest, mainly consisting of mixed conifer forests, mixed with large swathes of deciduous trees of various kinds. The ground is hilly, with valleys and depressions, and littered by large mossy boulders. There is a lake in the northern end. The serene ambiance under the dark trees is like something out of a fairy tale. At least, it used to be that way.

The forest was “discovered” during an excursion in plant biology in 1910, led by professor Rutger Sernander. He described a primeval forest with huge spruce trees, almost a meter in diameter, and enormous juniper bushes. It would later be revealed that the forest was basically untouched since the late 18th century. During the coming decades, Sernander worked hard to make the forest a natural reserve to protect the unique environment. A reserve finally was established in 1966, twenty years after Sernander’s death. The only human involvement for the last 250 years has been Länsstyrelsens work to keep the pathways open by removing fallen trees. No forestry has been conducted.

Fiby urskog is probably Uppsalas most famous natural reserve. It is a spot for school trips, mycological excursions and relaxing forest strolls, and the number of visitors is large enough that the forest is suffering from significant wear and tear. Länsstyrelsen thus has the right to close certain areas from public access.

The drought and the spruce beetle

As stated by the sign, the reserve is today closed, although it is not forbidden to enter. The reason is the large spruce beetle attack that has ravaged Sweden and large parts of Europe all since the severe drought of 2018.

The spruce beetle is just few millimeters large. As the name suggests, it digs tunnels into the bark of spruce trees, and deposits its eggs within. When they hatch, the larvae eat the bark, and once the beetle is developed it keeps on eating for a few weeks before digging itself to freedom and flying off. The spruce puts up a good fight, however. During normal conditions, the beetles are no match for a healthy tree, and they go primarily for stressed or diseased ones. But every such tree will give rise to a large number of new beetles in the next generation, and if many trees in a small area are stressed simultaneously, by drought, for example, the amount of beetles can grow large enough to kill neighboring healthy trees as well. This tends to happen after around 4 000 attacks on a single tree. Just as for the elm disease, it is therefore important to remove dead trees well before the beetles emerge. That happens approximately 8-10 weeks after the eggs were laid, but the trees should preferrably by cut earlier, because fully developed beetles can survive in the large chunks of bark that fall off during harvest.

The ongoing outbreak is still driven by the momentum it received during the drought of 2018, but has since lost a lot of its ferocity. Removing the attacked trees has not had much effect on this decrease – there has just been too many of them. Seven out of ten trees that should have been removed have been left standing. In nature reserves, however, dead trees are a problem even during smaller outbreaks. The guidelines may prohibit human interference, and even when they do not, the search for attacked trees is very resource-demanding. This means that bark beetles may cause greater damage in nature reserves than in production forests (indeed, in many cases one reason the reserve was established in the first place). This is further enhanced by the fact that the beetles prefer large, older trees, of which there are many in the reserves. This sometimes cause tension between government and forest owners, since the production forests close to the reserves of course also can be attacked. Or the other way around – since a large outbreak in a production forest may spread into a reserve where counter actions are prohibited or hard to administer.

Closed reserves

The outbreak in Fiby urskog is over. Almost every large spruce has been killed, and there are no more around for the beetles to live in. The dead trees rot quickly and can break or fall even in weak wind gusts, which is why it is considered dangerous to visit the forest. This is the reason that Länsstyrelsen advises against visits. But another reason is that it is pretty much impossible to move about in the reserve without having to constantly climb over large tree trunks. It looks as if it was hit by a hurricane that took everything with it. Or perhaps rather a tornado, because the trees lie in all kinds of directions.

This is not likely to change any time soon. As long as the outbreak continues, it is dangerous as well as meaningless to clean up the pathways, and it might not happen before every single spruce tree has fallen. Also, Länsstyrelsen lacks funding to deal with this very demanding workload. Fiby urskog will not greet visitors in a long time yet.

Fiby is not the only reserve in Uppland suffering this fate. To date, six other reserves are closed. The reserves will remain reserves also after the beetles are gone, but the forests that was to be protected will look very much different, and no 200-year-old spruce trees are likely to survive. Such trees are very rare outside the reserves, and for every attacked reserve they grow fewer still, for visitors to experience and for the species dependent on them to live on. The ravages of the spruce beetle affect us in many ways – not just through the losses of the forest industry, but also limiting ours and other species access to old spruce forests.

Formal obstacles to action

Fiby urskog is, like many older reserves, an example of how guidelines written with the best of intentions may lead to a valuable environment’s destruction rather than it’s salvation. The purpose in Fiby is phrased as to “preserve biodiversity and natural areas by allowing the area to develop freely without any human interference”. The guidelines are focused on what may not be done, and one of thirteen specifically formulated prohibitions cover “harvesting, clearing, cultivating, or conducting any other action of forestry or in any other way harm living or dead trees and bushes or other vegetation.” It is easy enough to understand the thought process: here is something worth protecting, and to do so we prohibit any kind of action. If there are 200-year-old spruce trees, we must protect them by making sure they are not cut down.

But because of the spruce beetles, the result is the very opposite. In Fiby as well as Örups almskog, each dying tree contributed to a higher infection pressure on the trees that remained. If the goal was to protect what existed, the primeval forest or the unique elm forest, then the laissez-faire-approach of the guidelines was counter-productive.

Länsstyrelsen has the option to seek dispensation for circumventing the guidelines of a reserve, but never from its overall purpose. Since “develop freely without any human interference” is written into the purpose of the reserve, no dispensations could be granted, and it was thus formally impossible to protect the reserve from the beetle. However, in the case of Fiby 2018, protecting the forest never was a possibility. The outbreak was by far the most intense on record, and developed very rapidly. Länsstyrelsen would have had to identify a very large number of attacked trees already during the fall of 2018, and then harvest them all in early 2019, which would have been difficult for several reasons. For one, the same drought affected not just Fiby, but every reserve in the county. And even if such considerable resources could have been mustered, the harvest in itself would have brought new risks since many healthy spruce trees would have ended up in the edges of the clearings, and such exposed trees are much more susceptible to beetle attacks than trees in the shadow of the forest. On top of that, Länsstyrelsen would have had to publicly defend the decision to clear-cut a large area within a popular natural reserve – a pedagogic challenge to say the least.

But during normal-sized outbreaks, a purpose phrased less stringently can make it easier to protect the forest. The reserve Granliden in north-eastern Uppland was established in 2017. Its purpose is “to preserve the calciferous conifer forest and marshland forests with ecosystems and biodiversity”, which is to be done by “conducting actions beneficial to prioritized species”. Such phrasing does not require dispensation for the feeling of, for example, spruce trees attacked by spruce beetles.

But even when such dispensations could theoretically be granted, they are practically difficult to use against spruce beetles. 150 of the reserves of Uppland is manged by Länsstyrelsen. The government searches for attacked trees in the spring to be able to fell them before the hatching of the beetles in the early summer, but dispensation requests takes months to administer. More than one generation of bark beetles can hatch in the reserve before the bureaucratic process has run its course. An exception is when spruce trees are felled in winter storms, and a dispensation can allow for removing the bark of the trees, or the trees themselves, before the beetles hatch in the spring.

Limited resources

This is why Länsstyrelsen focuses mainly on such reserves where actions are allowed without dispensations, and where the spruce forest is instrumental to the purpose of the reserve, such as in Granliden, mentioned above. The work is conducted by helicopter, dogs trained to discover attacked trees, and by manual search efforts on ground.

Länsstyrelsens beetle-fighting unit basically consists of two people. They describe it as impossible to address more than a fraction of the 150 reserves. Also, summer is the most important time for this endeavor, which collides with vacation. Demands for time-consuming procurement for tasks such as the felling of trees and flying a helicopter also affects the possibility to fulfill the task in time.

Such limitations also affects the establishment of new reserves. It is expensive to conduct the seek- and cleanse-efforts that is required to actively try to protect forests against spruce beetles, but it is very cheap to leave the reserves to their own devices. Sometimes, a free development type of purpose is chosen, even though a greater freedom of action would better serve to protect the environmental values at hand.

In conclusion, two types of deficiencies are aggravating damage in forest reserves. One is purely financial. The spruce beetle outbreak is too vast for more than a handful of the reserves to be protected by the financial resources available to Länsstyrelsen today. Nature preservation costs money, and how to prioritize natural reserves is ultimately a political question.

The other is a historical lack of knowledge of the devastating potential of forest pests and pathogens. That has lead to purposes and guidelines that prohibits counter actions that would have been necessary to limit the damage to the reserves. The understanding of forest pathology today makes it possible to avoid such mistakes. But the future will present new challenges after the spruce beetles are gone, which also must be met by new knowledge. In the work to develop this knowledge, SLU Forest Damage Center plays a crucial role.

Written by: Mårten Lind for SLU Forest Damage Centre